Law professors are apt to say "hard cases make bad law" and the

U.S. Supreme Court's recent decision in Mayo v. Prometheus Laboratories certainly

falls into this category. In a unanimous decision issued on March 20, two

patents that Prometheus had sought to enforce against Mayo Laboratories were

struck down because the Court concluded that the patent claims were directed to

natural laws and, hence, not eligible for patent protection.

The decision,

authored by Justice Stephen Breyer, has sent a shockwave through the

biotechnology industry because the Court's reasoning may lead to the demise of

diagnostic-method patents and remove the financial incentives that are

currently propelling the growth of personalized medicine. If Breyer's reasoning

is broadly applied, it is also hard to see how any diagnostic or even medical

treatment method claim can survive scrutiny.

The principal claim at issue in

the Mayo case recited a first step of administering a drug to a patient and a

second step of measuring the level of a particular metabolite in the patient's

blood and a "wherein" clause that described a level above which there

is a likelihood of harmful side-effects and below which the drug dosage may be

ineffective. The claim was drafted this way to cover any supplier of an assay

that would measure the particular metabolite.

The Court found this

"wherein" clause to be, in essence, an appropriation of a law of

nature and not the sort of thing that should be patentable. Breyer compared the

claim to Einstein trying to patent E=MC² or Newton trying to capture the law of

gravity in a patent. Relying on a decision from the early days of the age of

computers that found claims to a mathematical algorithm to be unpatentable

because the claims were "so abstract and sweeping as to cover both known

and unknown uses" of the formula, Breyer reasoned that the Prometheus

claims would likewise "risk disproportionately tying up the use of

underlying natural laws, inhibiting their use in making further

discoveries."

But was the discovery claimed in the Prometheus patent

truly an abstract law of nature? The patent solved a known problem, namely

selecting the right dosage for a very specific class of drugs that patients

metabolize differently. Because of the metabolic differences, a dosage that is

good for one patient is not necessarily good for another. The patent claim

recited the metabolite levels that were too high and those that were too low —

in essence identifying the sweet spot for therapeutic efficacy. This was a

practical application of science, not an abstraction like the law of gravity.

The

problem with the Court's reasoning is that every diagnostic invention is at its

core a discovery of a natural correlation between a biomarker or other analyte

and a medical condition. Historically, the question that governed patentability

of diagnostic methods, such measuring prostate-specific antigen as an indicator

of prostate cancer or high-density lipoprotein as sign of unheathy cholesterol,

has been whether the correlation discovered by the inventor was new and

unobvious to one skilled in the art — not whether the correlation embodied a

law of nature. How can any diagnostic method claim still be eligible for patent

protection if the law now precludes diagnostic methods that rely on a

scientific principle or law of nature? Would Breyer prefer diagnostic methods

be based on lucky guesses or Ouija board results?

Though not at issue in the

Mayo case, the Court's logic in the Mayo decision also casts a shadow on

method-of-treatment claims. For more than 200 years, the U.S. patent laws have

allowed patent protection — in the form of method claims — for new and

unobvious medical treatments with known drugs or agents. Many other countries

do not allow patent claims for human treatment but the U.S. laws do — or did.

Congress has from time to time debated the value of allowing method of

treatment claims. Several years ago Congress did impose some limitations on

surgical methods (requiring that the claims also recite a novel surgical

instrument) but Congress did not abolish medical-treatment claims.

However,

the logic of the Mayo decision may put medical treatment claims into the

"patent ineligible" category, as well. For example, a claim such as

"treating a retroviral infection with an effective amount of AZT" (to

paraphrase the famous first AIDS drug patent) could be suspect since it could

also be considered to be a claim to a law of nature. AZT works by inhibiting

reverse transcriptase, an enzyme necessary to the retroviral replication. The

AZT inventors discovered this "law of nature."

A less ominous

reading of the Mayo decision is that the Supreme Court simply felt that there

wasn't enough meat in the Prometheus claim and perhaps a more specific

recitation of the assay steps would have passed muster. If so, then the

decision leaves to the lower courts the dirty work of sorting out how much more

specific a diagnostic claim must be.

This process of leaving it up to the

lower courts to divine the meaning of the Mayo case has already begun. A few

days after its Mayo decision, the Supreme Court granted a petition to review

another hotly contested case involving Myriad Pharmaceutical's patents on

isolated breast cancer gene sequences — and then immediately remanded the case

back to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, from whence it came,

to reconsider its decision in light of the Mayo ruling.

It is most

unfortunate that the Supreme Court's decision in the Mayo case only discussed

one claim of the Prometheus patents. There were several more specific dependent

claims in the Prometheus patents that explained how the assay should be

conducted, e.g., by measuring metabolite levels in red blood cells or by use of

high pressure liquid chromatography. The biotechnology industry and patent

practitioners would have benefited from some explanation as to why these claims

were likewise unacceptable. Instead, the Supreme Court just kicked the can down

the road.

- Tom Engellenner (adapted from my recent article in the National Law Journal)

This blog is for information purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice on any specific facts or circumstances. Under the rules of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, this material may be considered advertising.

This blog is for information purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice on any specific facts or circumstances. Under the rules of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, this material may be considered advertising.

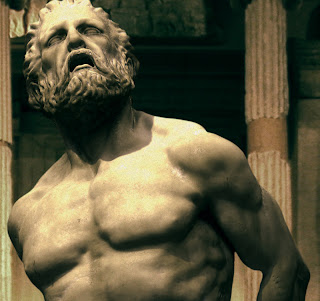

Nice picture of Prometheus (the statue).

ReplyDeleteThis is a bull-in-the-china-shop outcome that all reasonable patent practitioners should loudly criticize with no deference due to them who wear black robes but understand not the harm they do.

The ultimate take-away that your average inventor will understand is that the courts are not your friend (see also SmartGene v ABL) and Congress is not your friend (see America Invents (No More) Act of 2011). So why bother? Why bother if at the end of all appeals you show up in front of a blatantly anti-inventor Supreme Court?